By Fraser Perkins —

The Climate Crisis will likely lower Mono Lake levels for three reasons: less runoff from the watershed and streams, higher evaporative losses, and less precipitation falling directly on the lake.

The Climate Crisis will likely lower Mono Lake levels for three reasons: less runoff from the watershed and streams, higher evaporative losses, and less precipitation falling directly on the lake.

A lower lake level will have three major consequences.

- Mineral concentrations in the lake will increase, threatening the brine shrimp population, the major food source for tens of thousands of migrating birds.

- More lakebed will be exposed, leading to severe air pollution.

- Lake islands will become peninsulas, threatening the California Gull breeding grounds. Coyotes cross easily to the nesting sites when the islands become peninsulas connected to the shoreline.

Gambling aficionados whizzing up Highway 395 from LA to Lake Tahoe pass Mono Lake just north of Lee Vining. On initial inspection the Lake offers little more than a moonscape vista devoid of boats, water-skiers, trees, casinos and frankly much of anything of interest to the uninitiated. Closer inspection confirms the initial impression. Strange smells emanate from a lakeshore punctuated by clouds of flies. Come in spring and the lake is green, an apparent victim of algal blooms, mining tailings, or something more sinister. Come in late summer and while the lake is blue*, it lacks the iridescent, shimmering sparkle of Lake Tahoe.

Looks deceive. Beneath the surface of Mono Lake lies a food factory on ”steroids”. Trillions and trillions of tiny brine shrimp, each no longer than a fingernail, wriggle endlessly in pursuit of either food or mates. The biggest fans of this teeming, primordial, biologic soup are neither fish, (the lake has no fish), nor people, but birds…lots and lots of birds. Phalaropes and grebes by the thousands feast on the shrimp. For the two species of phalaropes on their annual migration south, July and August at the Lake is the critical link between breeding grounds in Arctic Canada and wintering playas in Bolivia and Argentina. Remove Mono Lake and the birds fail to complete a migratory rhythm stretching back millennia – they die from starvation.

In geology-speak Mono Lake is a terminal lake. Water washes in from the Eastern Sierra in the form of both streams and watershed baseflow and remains trapped until evaporation – there is no exiting stream. Left alone the annual variation in lake level is about four feet. Besides seasonal variation, dry years see lake levels drop, only to rebound during the occasional wet year. Run-off water also contains minute amounts of minerals. Over hundreds of thousands of years, stream inflow has brought chlorides, carbonates, and sulfates to the lake – resulting in a “triple” lake. This same process of desiccation, evaporation and replenishment repeats itself throughout the Great Basin.

There is one crucial difference between Mono Lake and all other Great Basin terminal lakes including the Great Salt Lake – Mono Lake is protected**. Other inland lakes dot the landscape, but most are too small to support a continuous thriving population of brine shrimp. Still others have lost their inflow because of human diversions for agriculture, cities, and industries. Owens Lake, between Olancha and Lone Pine, lost its battle with the LA DWP long ago and remains little more than a carcass of a lake. Whatever water exists is the result of a court battle waged to prevent lakebed dust from swirling into toxic plumes swathing the Sierra Nevada Mountains in the worst air pollution in the nation. Great Salt Lake is on the precipice of terminal decline. Utah leaders understand the risk but wilt before the onslaught of pressure to divert water for development. Elected officials retarding unbridled growth have short political life spans in Utah.

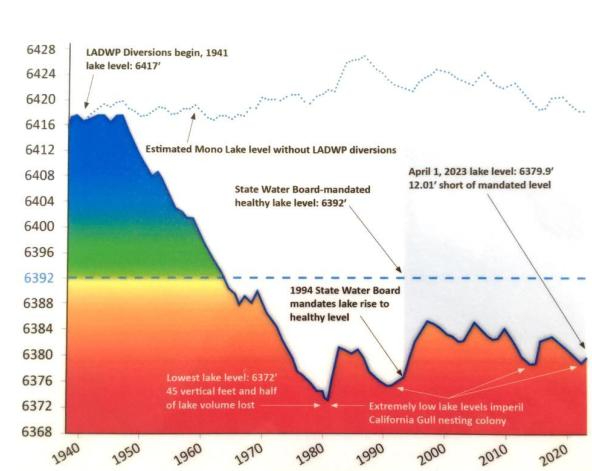

In 1941 Mono Lake changed. The LA DWP began water diversions away from the lake by damming inflowing streams, shooting the fresh water through an eleven-mile tunnel under the Mono Craters, and dropping it into the Owens River where it entered the LA Aqueduct system. As the accompanying graphic from the Mono Lake Committee shows, the impact on Mono Lake was dramatic – the lake level collapsed from a normal level of 6417’ to 6372’ above sea level in less than 40 years. Lake extinction loomed in the form of three problems. The salinity of the lake increased to the point where brine shrimp expended so much energy expelling salt, they couldn’t reproduce. Exposed lakebed allowed the relentless winds to swirl the mineral rich soil into toxic air pollution plumes. Negit Island in the north side of the lake became a peninsula, allowing coyotes to devour the eggs and chicks of the California Gull Rookery located there.

Mono Lake avoided irreversible decline through the tireless dedication of local leaders, scientists, and activists who formed the Mono Lake Committee to preserve and protect the lake. Their timing proved excellent. In 1983 the California Supreme Court ruled that under the Public Trust Doctrine, the state has a duty to protect lakes and streams for the benefit of the public. The California Water Control Board issued a ruling in 1994 that mandated annual allowable LA diversions based on the lake level as of April 1 of the given year. And here we must credit where credit is due. The Republican mayor of Los Angeles, Richard Riordan, chose not to fight the State Water Board and accepted the ruling. Whew! A story with a happy ending…yes?

Not quite. The expectation in 1994 was that the lake level would take twenty years or so to rise to the mandated level of 6392’. As you can see from the graphic, for a time the lake level rose but the punishing droughts of 2000 – 2022 blocked progress. Despite the water bounty of last winter, the date for reaching the mandated level remains elusive. Now consider Climate Change. Warmer temperatures not only threaten stream flows into Mono Lake but will also cause greater evaporative loss in the summer. Warmer temperatures will decrease another key source of lake water, rain and snow falling directly on the lake. To reach the mandated level of 6392’ the Mono Lake Committee has asked the State Water Board to revise the current allowable water diversions. Climate Change is forcing all of us to adapt. For more information on the Mono Lake Committee, please click.

One final note. To see an early morning murmuration of birds over Mono Lake against the backdrop of the Mono Lake tufa towers and our beloved Sierra Nevada Mountains is an unforgettable moment which stays with you forever. I invite you to take a break the next time you head north on Highway 395. Turn east on State Highway 120 and go five miles to spend an hour or so at South Tufa. Gamblers are always welcome!

*The lake normally turns color from springtime green to summertime blue as the brine shrimp gobble up the algae which line the bottom of the lake. As algae disappear the lake turns bluer.

**The protection of Mono Lake comes from three factors: highly motivated local support, lack of significant population, agriculture, or industry around the lake, and dealing with only one opposing entity, the LA DWP. Mono Lake may be one of the best-preserved terminal saltwater lakes in the world, as relentless stream diversions threaten saltwater lakes everywhere.

Leave a Reply